Like Butch Berry, plenty of people are sad that kids “don’t know how to play in the woods anymore.” But Butch, who leads the restoration of Springfield Woods, is actually doing something about it. He’s pulling out poison ivy and cutting paths, and getting neighbors into the woods to experience nature and get invested.

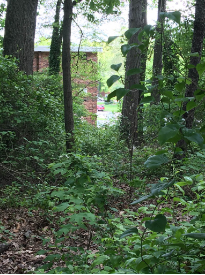

Butch spent idyllic days of his 1960s childhood in Springfield woods, foraging for berries and playing cowboys and Indians. After college and a couple of decades away from Baltimore, he came back to his old neighborhood in 2001. In the meantime, the woods were being used as a dumping ground and had become impenetrable with overgrowth. To Butch, it seemed that everyone accepted that as just the way it was, and didn’t notice the woods anymore. He decided to change that on January 1, 2012.

Since then, with support from Baltimore Green Space’s Forest Stewardship Network, Butch has worked to save a lovely forest patch from invasive plants, and in the process turned it into a real-life laboratory for students at all levels.

In 2012, the invasive plants were “higher than any of us,” Butch recalls. He decided to start the clean-up at the stream – but first he had to find the stream. It was covered by vines and clogged with junk, and people thought it had dried up. Baltimore Green Space put Butch in touch with the Johns Hopkins President’s Day of Service, and volunteers from a sorority helped Butch pull old lumber, vacuum cleaners, and five bags of glass from the stream. Soon he could find the source: a spring whose water is clean enough that salamanders and turtles can live there. And the soil appears uncontaminated too. Research coordinated by Baltimore Green Space shows that the it includes a good layer of organic material, as in larger rural forests.

Initially the work of restoring the Springfield Woods focused on clearing out the junk, including dog cages that Butch suspects were used for raising pit bulls. As he got deeper into the process, Butch learned about natural spaces from Baltimore Green Space and partner organizations, including the Maryland Forestry Service, the University of Maryland Extension, the University of Baltimore, College Park, and the Maryland Natural History Society. Now he has a plan. “We’re trying to save the good stuff, and take out all the invasives.”

People in the neighborhood have begun pitching in, and they don’t let contractors dump construction trash there anymore. Volunteers from local private schools come to help too. It’s very important for helpers to know which plants need to go and which should stay. Butch is philosophical about the delicate balance required to educate enthusiastic helpers without scaring them away.

To make the forest more welcoming Butch names parts of the woods, complete with wooden signs. Some examples: “Fox Den Way”, where there actually is a fox den. “Sunset View”, at the top of a westward-facing hill that was originally nothing but briars and now is a shady spot with cool cross breezes. “Gathering Place,” a clearing with wild flowers. The more he does, the more he thinks of to do – and a big focus is children. He wants to teach kids to love the forest, and he thinks about organizing a program of campfire stories held in the patch to show kids not to be afraid of natural places. He wants to build a fence at the edge of Sunset View to make it safe for young children so that public schools can bring kids for walks. He wants to label the trees. Butch notes that people are scared of wolves in the patch – but there are no wolves, just foxes, opossums, and raccoon.

Springfield Woods’ role as a real-life laboratory for teaching students at all levels is very important to Butch. From school kids to PhD candidates, all are learning about urban forests and native plants. While he plants pecan, persimmon, and elderberry trees for the wildlife, Butch thinks about planning foraging hikes to show his neighbors a natural world they haven’t noticed. It’s one more reason for them to love and protect a treasure right at their feet.

If you’d like to get involved at Springfield Woods – or join the Forest Stewardship Network to learn how to work in a forest patch in your neighborhood – send us e-mail at [email protected] or call 813-530-8166.

Be the first to hear about exciting events, news, and opportunities.

[email protected]

(813) 530-8166

2100 Liberty Heights Avenue

Baltimore MD 21217

Facebook | Instagram | Twitter